Premet: Home of the flapper

- Feb 8, 2018

- 7 min read

Forgotten 1920s fashion label was led by series of female designers

Barely remembered today, Premet, 8 Place Vendome, was among the most innovative Paris couture houses of its time, spanning the late belle epoch to the jazz age. Best known for "La Garconne” (or “The Flapper”), a black dress with a white collar and cuffs introduced in 1923, Premet was unique in that its inspiration didn’t depend on a single personality, but maintained a tremendous reputation through a succession of creative designers, all of them women.

Despite their number and variety, these couturieres managed a cohesive style that appealed equally to their exclusive clientele and to mainstream consumers who purchased retail copies of Premet designs.

“A certain daring has always characterized the creations of Maison Premet," Vogue pointed out in 1915, "a daring stamped with conservatism, and never approaching the bizarre."1

Mme. Premet (possibly Madeleine Premet) was the original designer for this house, founded in 1909 in the Faubourg Saint Germain enclave of Paris' Left Bank.

The vision of Mme. Premet

Premet quickly became a favorite with families of the French nobility, and when she relocated to the Place Vendome in 1911, her establishment occupied "an entire building of six floors."2

Incorporating in September 1911, Premet enjoyed her first "marked success" with the line of draped evening gowns she included in that year’s fall-winter collection.3 Two of these dresses were the first Premet designs to be photographed for Vogue, appearing in the magazine’s February 1, 1912 issue.

Just as the house was taking “first place with the seasoned leaders” of Paris fashion, dressing top actresses as well as aristocrats, Mme. Premet retired from full-time designing, employing as an assistant a young “modelist” from the house of Jeanne Hallee.4

The newcomer, Mme. Lefranc, brought with her, according to Women’s Wear Daily’s Edith Rosenbaum, a number of workroom staff from the dressmaking house of Maubaux & Dugdale.5 The correspondent found the resultant change in the Premet line for spring 1912 to be a significant one. The acquisition of Lefranc had injected, Rosenbaum wrote, “a new spirit into the collection.”

Vogue concurred, stating that Premet was now a house that was looked to each season for gowns that would exert “a considerable influence on the modes.”6 It was at this time that Premet’s sway with American department stores and import houses began — among those selling originals and adaptations were Henri Bendel and Haas Brothers in New York and Marshall Field in Chicago.

Lefranc improved on Mme. Premet’s favored draped skirts, adding a number of versions to the house’s collections over the next few years; one in particular, a white velvet, fur trimmed reception dress for the Riviera, was a fall 1912 hit.

Innovations under Mme. Lefranc

The house of Premet’s spring 1913 collection was one of its most publicized due to a range of extremely short skirts that revealed wearers’ ankles and lower legs. These were the shortest lengths so far approved by the couture, although a street fad for ankle-exposing hems had been building for a few years.

Throughout World War I, Premet continued to be noted for its abbreviated skirts, a trend generally misattributed to Chanel. By fall 1914, Premet was alone in showing calf length skirts, an extraordinarily bold statement.7 As Vogue commented the following year: “Premet first dared the short skirt which has grown shorter and shorter until it cannot shorter grow.”8

Another style Lefranc introduced in her spring 1913 line for Premet was the Medici collar, plunging in front and standing at the back. Mme. Premet herself, still involved in house operations but no longer designing, promoted the collar by appearing in it on several notable occasions.9 The Japanese collar was another popular new neckline ascribed to Premet although there was some discussion in the fashion press as to whether Lefranc had copied it from the Callot Soeurs. Premet’s business manager M. Winter was interviewed by Women’s Wear Daily about the dust-up, and he presented house documents as well as published evidence to prove his firm had initiated the look.10 M. Winter was assisted in the direction of the house by M. Mathon and Mme. Premet.11

For Premet’s fall 1913 collection, Lefranc was one of the first couturiers to shift from the tapered line to a flaring silhouette, and after this became a general trend in other designers’ shows the following spring, her skirts were still widest of all.12 One of her patrons, Comtesse de Talleyrand, modeled a very bouffant Premet gown for the June 1914 issue of Les Modes.

Lefranc, like her predecessor, was attractive and regarded as a trendsetter; when she appeared at the races with a troupe of models, her gowns were as admired as theirs.13

In May 1914, Mme. Premet herself retired from active work, the announcement appearing in the Paris magazine Confectionair and reprinted in Women’s Wear Daily. It was explained, however, that the founder would “retain her interest in the firm.”14

Mme. Renee and the vicissitudes of Premet

An even more surprising development that year was the sudden death of Mme. Lefranc from an undisclosed illness.15 Her obituaries credited her with advancing the current taste for simplicity. According to reports, Lefranc’s last public appearance was at Longchamp, the last client she met with was the famous Forzane and the last dress she designed was of gray chiffon with a pleated skirt.16

Mme. Premet returned to the salon to supervise production temporarily until a replacement for Lefranc could be found. Meantime, rumors abounded that the house had offered an unnamed dressmaker a salary of 250,000 francs a year to take over as designer for Premet.17 One name put forward was Pierre Bulloz, former assistant cutter for the house of Beer, but the report proved inaccurate.18

A little over a year later, Mme. Renee was hired as Premet’s new designer.19 Her original interpretations of the leaner line that was emerging by the end of the war were popular with clients, and in keeping with an unspoken tradition, she was noted for her own beauty and dashing style.20 Renee’s fame grew to such an extent that she left Premet in 1918 to open a house under her own name, showing her first independent collection in February of the following year.21

Mme. Charlotte and Premet’s great period

It was after Renee’s departure that the most celebrated of all the women to helm Premet came in as designer. Mme. Charlotte Revyl was a former midinette in various fashion houses, rising in the ranks until she was nabbed to assume duties as chief modelist for Premet.

Apart from her clever aesthetic, Mme. Charlotte found great personal fame as a pacesetter in her own right. As Paul Nystrom pointed out in The Economics of Fashion, Charlotte was “one of the most beautiful and picturesque women in Paris.”

Her high spirited personality added to her chic, which in turn was underscored by her prematurely white hair, close cropped and tinted mauve. The result of her hairdresser’s mistake, the style became her hallmark. Robert Forrest Wilson noted that everything about Charlotte was fodder for the fashion media – her love of sports, her chic home, her party-going.22

From her arrival at Premet in 1918 until 1930, when she resigned to open her own salon, Charlotte had an enormous impact on fashion direction. Unique cuts and details defined her work but it was the simplest of simple black dresses that became the most successful design the house ever launched. Produced three years before Chanel’s supposedly pioneering “little black dress,” it was known as “La Garconne,” borrowed from Victor Margueritte’s sensational lesbian-referencing novel of the same name.

La Garconne

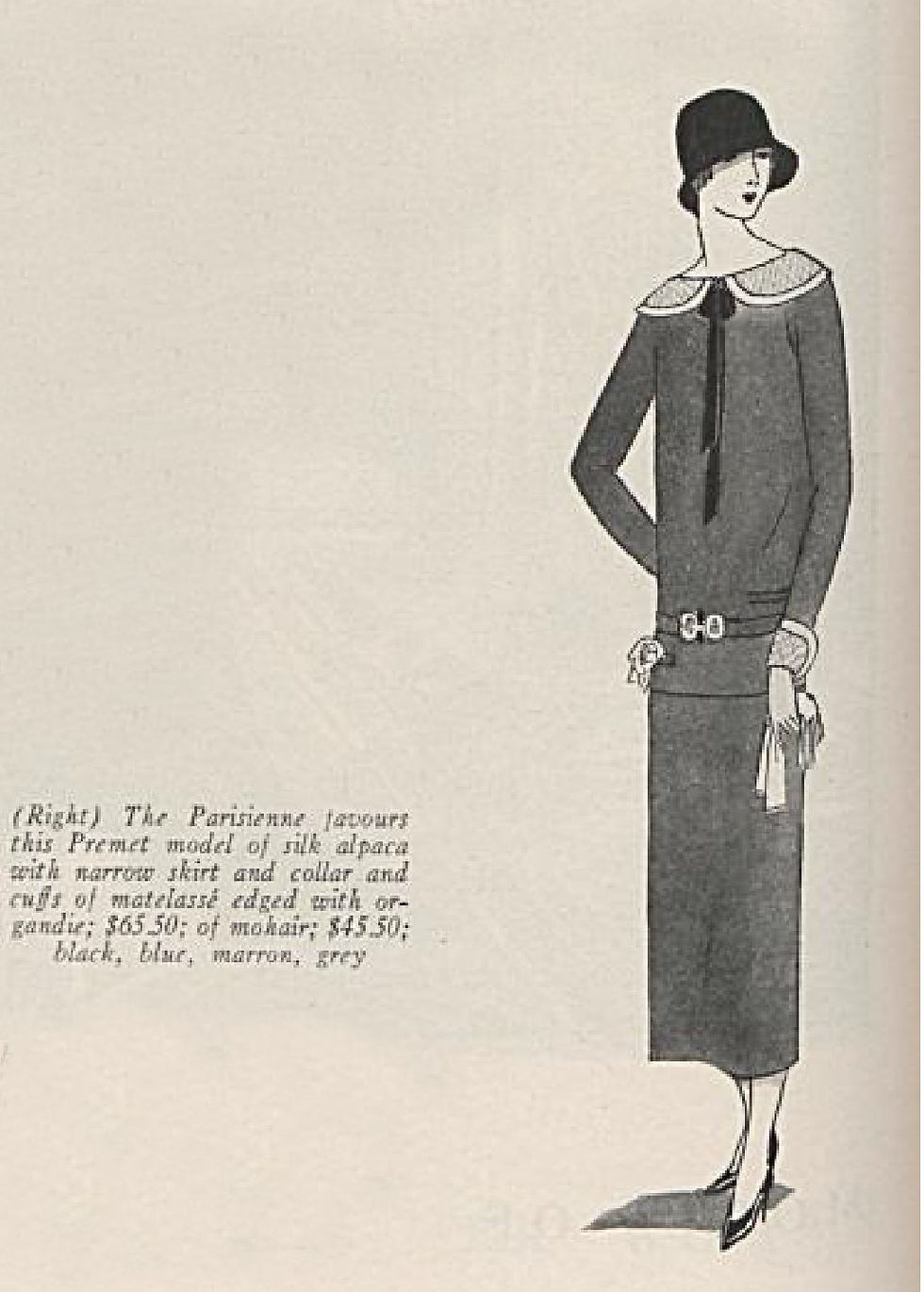

In a 1950 retrospective feature, Women’s Wear Daily called La Garconne the “most copied and talked about” dress of the 1920s. The paper further described it as a “two-piece frock with Claudine collar that incited even the old and obese to adopt schoolgirl modes.”23 In truth, the original dress was one-piece but it so resembled the era’s juvenile jersey blouse and skirt combination that it was often later reproduced as a two-piece. Some original versions of La Garconne had a slim scarf or tie under the collar, gauntlet cuffs, a belt, even pockets. 24

Vogue referred to Premet’s La Garconne as the “most celebrated single dress the world ever knew,” adding that its success was in keeping with the house’s “habit of creating best-sellers, as there is seldom a Premet collection in which one or two dresses do not show wild-fire symptoms.”25 Nystrom claimed “millions of women wore the style although the house itself made only about a thousand.”26

Charlotte created the first example of La Garconne in 1922 but it drew little notice from customers, and only one foreign commercial buyer ordered a licensed copy. It wasn’t until Charlotte herself wore the dress the following season that it took off as a “must have” for her elite clients. It also impressed American department store buyers who imported copies in record numbers.

The next year, as more and more average women adopted La Garconne via mass marketed reproductions, wealthy ladies started to abandon it. The house of Premet, however, didn’t eschew the popular dress, featuring variations through 1925.27 Premet gowns, even as late as 1930, echoed the original design.

Premet’s end

As far-reaching as La Garconne became, it was a last hurrah for Premet as an innovatory label. In 1929 the house moved to smaller premises at 126 rue la Boetie and by the end of the next year, Mme. Charlotte left to establish her own couture brand, Charlotte Revyl, at 21 Faubourg Saint Honoré. Before her departure, Charlotte trained the legendary Alix Gres.

As the 1930s progressed, the name Premet became increasingly associated with its luxury accessories and perfume franchise, operated by Paul Premet, possibly a son of the house’s founder. Two of Premet’s best known fragrances in 1931 included “Le Secret de Premet” and “Pour un Oui.”28

Although the original Premet filed bankruptcy in 1932, the house was reorganized and survived into the next decade. Charlotte Revyl also continued as an important label, branching out into ready-to-wear and licensing contracts before closing in the 1940s.

Inger Sheil and Antoine Bucher contributed research for this article.

NOTES

1. Vogue, 1 Aug. 1915, 58.

2. Ibid, 15 Nov. 1926, 32.

3. Ibid, 1 Apr. 1912, 108.

4. Ibid.

5. Women’s Wear Daily, 13 Mar. 1912.

6. Ibid; Vogue, 1 Sept. 1912, 44.

7. Ibid, 1 Oct. 1914, 38.

8. Ibid, 1 Aug. 1915, 58.

9. Ibid, 15 Mar. 1913, 24-25.

10. Women’s Wear Daily, 13 May 1913 and 5 June 1913.

11. Vogue, 15 June 1915, 27.

12. Femina, 15 Dec. 1913, 685.

13. Women’s Wear Daily, 10 Feb. 1914.

14. Ibid, 13 May 1914.

15. Ibid, 4 May 1914.

16. Ibid, 17 Apr. 1914, 1 May 1914 and 3 July 1914.

17. Ibid, 26 May 1914.

18. Ibid, 3 June 1914.

19. Ibid, 12 Nov.1915.

20. Ibid, 23 Aug. 1918.

21. Ibid, 10 Feb. 1919.

22. Vogue, 15 Nov. 1926, 154.

23. Women’s Wear Daily, 15 Aug. 1950, 55.

24. Vogue, 1 Nov. 1923, 80.

25. Ibid., 15 Nov. 1926, 30.

26. Paul Nystrom, The Economics of Fashion, New York: Ronald Press, (1928), 22.

27. Women’s Wear Daily, 11 Feb. 1924 and 22 Oct. 1925.

28. Femina, June 1931, xxxviii.

Comments